Duration: 6-8 Weeks

Checklist of previously completed work:

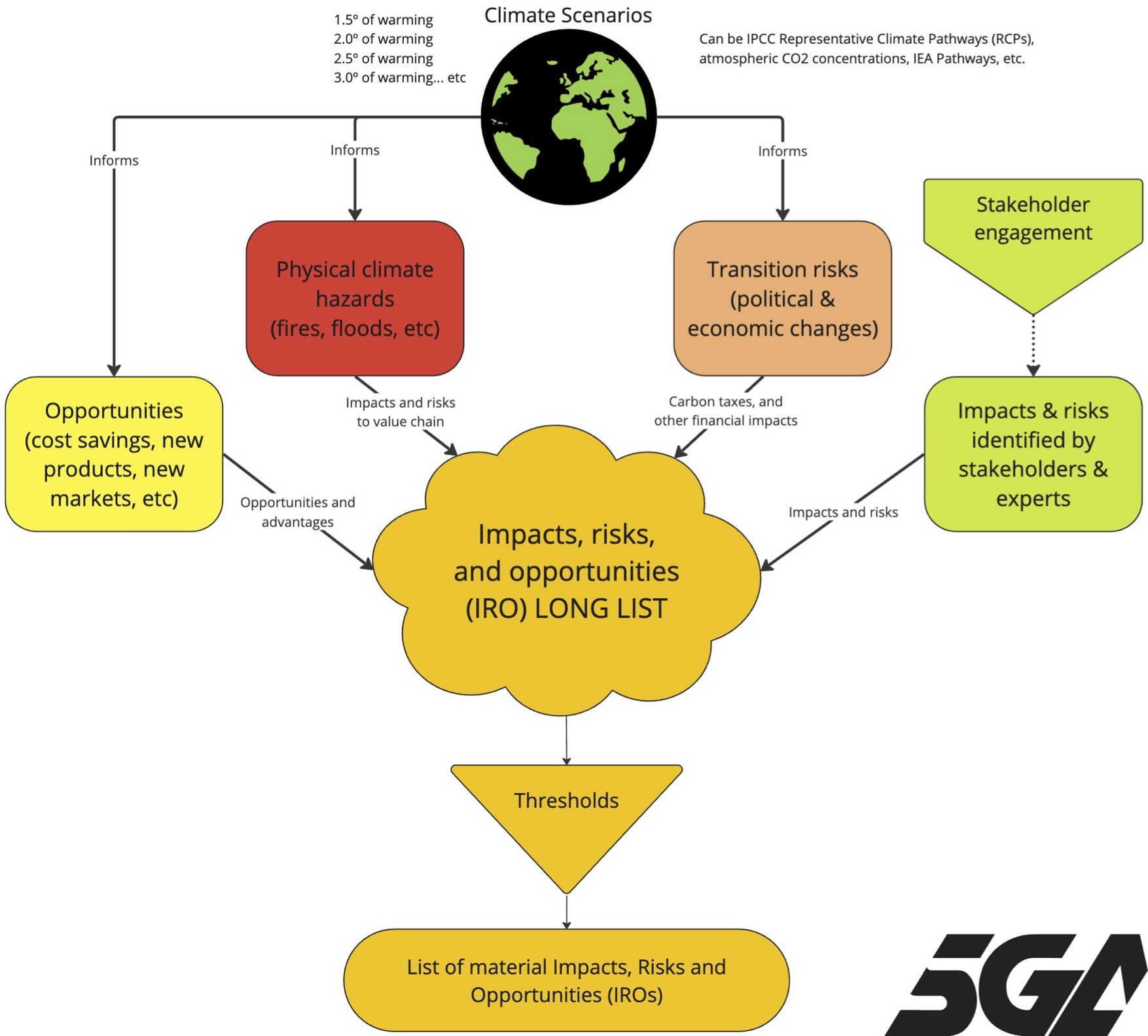

Double Materiality means considering both the impacts on people & planet from the organisation as well as the reverse – the impacts that people & planet may have on the organisation. In practice, this means combining the issues identified by the stakeholder engagement process in the Stage 2 ‘Preparation’, with an assessment of the risks and opportunities that you might face from climate change, as well as from society as it adapts to a changing environment. This will produce a ‘long list’ of potential material topics, which are then cut down to a list of actual material topics, by applying thresholds.

Some of the precise details of this stage are up to implementers to determine in response to the circumstances of each organisation. Larger organisations will be expected to undertake a more rigorous analysis that fits their more complex circumstance. EFRAG’s implementation guidance document IG1 specifically states that “the ESRS do not mandate how the materiality assessment process shall be designed or conducted by an undertaking. This is because no one process would suit all types.” (EFRAG IG 1, p.19) Instead “an undertaking shall design a process that is fit for these purposes based on its specific facts and circumstances, including consideration of the depth of the assessment, as per the requirements of ESRS 1 Chapter 3 and of the DRs regarding the materiality assessment and its outcome.”†

The process outlined below is intended as a starting point for game businesses, providing a minimum level of confidence in the double materiality assessment. Keep in mind that ESRS preparers must exercise some of their own judgment, informed by their understanding of their particular circumstances.

In future, the EU plans to develop sector-specific standards that will mandate specific, sector-relevant sustainability topics are addressed by specific industries. While these are more likely to affect high-emitting sectors like cement and steel, the SGA feels that it is advantageous to proactively establish our own sector-specific norms.

The image above illustrates the main components of the Double Materiality Analysis – with each component contributing part of the picture. At the end of the process, we are left with just the material impacts, risks and opportunities (IRO).

† ESRS 1, Chapter 3 is the section of the ESRS that explains “Double materiality as the basis for sustainability disclosures” and is worth reading in full; DRs refers to the “Disclosure Requirements” which are individual sub-topics within the Topical ESRS – for example, within E1 “Climate Change” a subtopic is “Disclosure Requirement E1-2 – Policies related to climate change mitigation and adaptation”)

In the previous Stage, your engagement with stakeholders will have identified the impacts that the organisation has on people and planet. The other half of the DMA process is to examine the risks that people (transition risks) and planet (physical risks) might have on the organisation. While doing this, opportunities will also become apparent along the way.

The results of this three-part analysis will be combined with your long list of actual and potential impacts from the stakeholder engagement process (see Stage 2: Preparation) and a materiality screening process will be applied to ranks issues by severity and likelihood of impacts.

Once ratings are in place, you will then be able to set appropriate materiality thresholds, to determine cut-off points below which issues are considered “non-material” and do not need to be disclosed. Items above the threshold are considered “material” and will need to be reported on. The final list of material topics will be carried forward into Stage 4: Data Collection and Gap Analysis.

The goal of this section of the DMA process is to identify the kinds of risks and opportunities from climate change that your organization may face in the years ahead, informed by the range of possibilities outlined by the latest climate science. To do this, we need to employ climate scenarios to understand the possible range of future risks and opportunities.

Climate risks facing game businesses can be placed into one of two buckets – physical or transition risks.

Physical risks are impacts from changing environmental systems, like increased duration of heat waves, more powerful storms, or changes to patterns of precipitation resulting in longer droughts and more intense flooding.

Transition risks are impacts of political and social changes as society, businesses and governments respond to the need to address climate change. This can take many forms, like increased costs from carbon taxes, higher electricity prices that incentivise energy efficiency, changing customer expectations, demands for greener products, and even changing access to credit or finance.

The potential impact and likelihood of both of these types of risks will vary depending on the way that society and the planet itself respond to emissions of greenhouse gases – under a higher emissions scenario, we will face more physical risks, while under a lower emissions scenario in which society takes more drastic action to curb emissions, we may face greater transition risks.

Opportunities also exist along the entire spectrum of future possibilities. This might include the ability to reduce costs through improving energy efficiency, or by installing solar panels to provide most of your own electricity needs. Opportunities aren’t limited to just saving money, they can also produce other benefits: like gaining a reputation for sustainability that helps to retain top employees, or the opportunity to attract climate-conscious customers with sustainable products.

To analyse the physical and transition risks and opportunities facing an organisation, we need a sense of the possible range of futures that we might face. This is where scenario analysis comes in, and it is a requirement baked into the ESRS. The topic of scenario analysis alone could be at least as long again as this page – and others have already written fantastic guides to the concept and fundamentals.

The Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) has developed a comprehensive and accessible primer on climate scenarios. They describe them as:

not predictions of the future, but rather projections of what can happen by creating plausible, coherent and internally consistent descriptions of possible climate change futures. They can also constitute plausible, coherent and internally consistent descriptions of pathways towards certain goals. So climate change scenarios can come in two different forms, projections “What can happen?” and goal-oriented pathways “What should happen?”, depending on the type of question they aim to answer.

PIK

For the purposes of ESRS compliance, we want to use climate scenarios to answer two questions for our particular organisation and context: 1) what can happen? and 2) how resilient is our organisation if this does happen?

On their own, a single scenario doesn’t provide much information. Their real value for decision-making is when they are used for comparisons:

As scenarios are not about predicting the future, a single scenario is virtually meaningless. Scenarios are rather used in pairs or larger sets to contrast different futures and choices. For example, scenario-driven climate policy analysis relies on comparing a projection without policy intervention (typically called baseline scenario) with a pathway towards a desired goal (e.g., the 2 °C goal).

PIK

While there are several possible sources for climate scenarios, the SGA recommends using the world-leading NGFS “Scenarios Explorer”, which contains 7 scenarios. Instructions on how to “use” these scenarios can be found here – the SGA can also help you to understand which scenarios to choose and how to interpret them for your organisation.

There are few “rules” about how to use scenarios for ESRS reporting as this is an area of emerging consensus and evolving best practices. However, the ESRS does specify some requirements.

First, physical risk assessment must consider “at least high emission climate scenarios” as well as “how [the organization’s] assets and business activities may be exposed and are sensitive to these climate-related hazards, creating gross physical risks for the undertaking.” (ESRS 2 IRO-1) This means analysis that applies at least one of the NGFS scenarios “fragmented world”, “NDCs” or “Current Policies” scenarios, and the types of risks that would eventuate for the organisation if these scenarios played out. (Assuming that you are using the NGFS scenarios)

Second, the ESRS also specifies that transition risk analysis considers “at least a climate scenario in line with limiting global warming to 1.5°C with no or limited overshoot”. This means considering at least one of the NGFS scenarios with high transition risks, such as “Net Zero 2050” or “Delayed Transition”.

When undertaking a scenario analysis, it is important to analyse risks and opportunities across different time horizons. The ESRS requires the analysis to consider risks and opportunities in short, medium and long-term time horizons. For the ESRS, short time horizon means, typically, the same period as the reporting time frame (i.e. one year), medium typically means up to 5 years, and long term means beyond 5 years. So for example, when you examine the physical risks your organisation is exposed to in the short term you are thinking about one year ahead, in the medium term about five years ahead, and long term means thinking about beyond 5 years – potentially out to milestone years, such as 2050, 2040 or other key dates on the road to net zero.

Physical risk analysis starts with the previous work done in Stage 2: Preparation. Make a list of the critical or essential locations of your operations and value chain. For each location, site, or element of the value chain you will consider its exposure to each of the physical hazard types required by the ESRS (fire, flood, storm, water stress, etc – see the SGA template for the full list as required by ESRS). Adjust the size of your location list to fit your organisational capacity. Larger organisations may need to list more value chain elements, and smaller organisations may only need 1 or 2 – for example, a main office and a crucial data centre might be all that is required for a company of 200 employees. For a company of 20,000 employees, a more rigorous process would be expected.

For each site or critical element of the value chain you will use the SGA physical risk assessment template to examine each risk and record whether the type of risk is material.

Assess the materiality of the risk by opening the link to the linked risk evaluation tool, and apply the applicable scenario(s) and year you wish to assess. In most cases, you may need to do this multiple times, as at least two scenarios should be addressed.

Some experience is necessary to interpret the output of these hazard representations, coupled with an understanding of the location or value chain component being assessed. The SGA can help with interpreting the output of these tools – reach out if you feel you need assistance in this aspect.

If the hazard tool shows a relevant hazard you will make a record of it, along with its “likelihood” and “severity”, and whether it For hazard types that are not applicable, mark them “not material” and write a short explanation why.

For example: if a flood risk map of your location shows an increased risk of a 1-in-100-year flood occurring, mark the risk as “potentially material”, and record the level of “likelihood” of the risk (the SGA template recommends a 1-5 point scale) along with the “severity” of the impact (also on a 1-5 point scale). If the expectation of events that cause severe flooding in the location being analysed goes from being 1-in-100 years to 1-in-20 years in the particular scenario, then the likelihood is increasing, and over a 20-year time horizon, at least one event of that scale would be expected, making its likelihood quite high. Similarly, if a hazard tool shows the degree of water stress in a location going from “medium” to “extremely high” under the scenario being considered then the severity of that hazard for a data centre that relies on a supply of water for cooling might also be considered to be quite high.

To be clear, many, if not most of the climate risk types the average game developer must consider are likely not to be material for typical organisations – but this will always depend on the location and context of each. The SGA template will help you to document your decision-making in this process and demonstrate the process you have taken to analyse the risks you may be exposed to.

In the CDProjektRED ESG report covering 2023, the following three physical climate risks were assessed as material. Other possible threats are likely to have also been evaluated and considered “not material”.

Take-Two in their TCFD climate risk report for 2024 identified the following physical climate risks. Elsewhere in the report it was stated that three scenarios were considered: IPCC RCP8.5 (business as usual), NGFS Disorderly: Delayed transition, and NGFS Orderly: Below 2°C.

Assessing transition risks is much like the process of identifying physical risks, and should be informed by scenario analysis. Here, instead of looking at scenarios that are high in emissions, lower emissions scenarios should be used as these may entail more dramatic transformations of society.

There is no exhaustive or simple approach to assessing transition risks – it is inherently a speculative and creative exercise that involves imagining what might be possible. Transition risks can come from changes in government or legislation, social attitudes, customer behaviour, or any other feature of society that might – as a result of mitigating or adapting to climate change. They can result in anything from higher operating costs to a loss of social license to operate.

Transition risks, like physical risks, can occur over short, medium, or long time horizons, and are typically classified as belonging to into one of four categories: Policy and legal risks, technology risks, market risks, or reputational risk.

Below are some examples of the transition risks that game companies have identified and disclosed in their annual reports:

Increased pricing of GHG emissions

Enhanced emissions-reporting obligations

Medium

Short

Substitution of existing products and services with lower-emission options and costs to transition to lower-emission technology

Energy transformation

Medium

Long

Changing customer behavior

Uncertainty in market signals

Rising cost of energy

Cost of market mechanisms used to achieve climate commitments

Long

Short

Medium

Medium

Increased stakeholder concern about climate action

Reputational risk from increasing expectations of how we address climate change

Short

Medium

Medium

Use the SGA template to describe the transition risks your organisation faces, applying the same assessment criteria as for physical risks: note the effect of each of your chosen climate scenarios on both the likelihood and severity of this risk eventuating.

Keep in mind that transition risks may not apply to the organisation’s specific locations so much as the operating environment the organisation finds itself within.

The SGA can also help here by running a transition risk workshop with you.

Opportunities are often closely related to the kinds of (physical and transition) risks identified. For example, a risk of high electricity prices might also present as an opportunity to reduce or avoid these prices by installing solar panels on office buildings, or through engaging in a power purchase agreement. A reputational transition risk from customers expecting more sustainable products might be an opportunity to appeal to a new segment of the market, or to attract positive brand sentiment by meeting sustainability targets.

There is less consensus about how to categorise types of opportunity but there is some overlap with the categories from earlier physical & transition risks. Once again, your use of scenarios should guide your identification of opportunities – lower emissions (faster changes) should mean more opportunities that stem from the changing political and social landscape as the transition proceeds, whereas higher emissions scenarios (slower change) might mean more opportunities to improve resilience, preempt physical risks, and adapt to our changing climate.

Not all opportunities have to be related to mitigating or offsetting a risk however – they can also be opportunities from new technologies, cost savings that from implementing process improvements changes or efficiencies, or any other beneficial outcome. One approach to identifying opportunities outside those that are connected to a specific physical or transition risk might be to consider each of the categories above (and below) and considering what opportunities might exist for your organisation in each. Keeping in mind the positive dimensions of the future we are trying to bring about might be helpful, as is applying some creativity and imagination (while still being plausible and connected to reality).

Below are some examples of opportunities identified by game businesses, and disclosed in their ESG reports.

Deploying eco-friendly solutions at campus

Transition to more efficient buildings, reduced water consumption, and more efficient use of space

medium term

short and medium term in the RCP 2.6 scenario

Being regarded as the gaming industry leader in terms of climate-friendly approach to business

Attraction and Retention of Talent

short and medium term in the RCP 2.6 scenario

(no time horizon given)

Use of lower-emission sources of energy

Participation in carbon markets

Shift toward decentralized energy generation

Medium

Long

Long

Development of new products and services – reflect shifting consumer preferences for lower-carbon goods

Medium

Management of relationships with suppliers to reduce the risk of delays and disruptions

Ability to influence customer and supplier (external stakeholder) actions to keep face with respect to climate agenda

There is a lot of room for improvement in our knowledge of this complex topic, and it is an area which has not yet achieved a significant consensus. Risk and opportunity identification is inevitably a situated practice that cannot be removed from the context of the organisation, the environment it operates in, and the make-up of its business, social and environmental relationships.

The SGA is committed to clarifying, simplifying and improving the process for game businesses and ensuring that climate risk assessments are sufficient to meet the seriousness of the threat of climate change while avoiding either exaggeration or minimisation.

Taking all the previous issues you have assembled via the stakeholder engagement process, and the DMA above, will give you one long list of topics. Each item should now have a materiality rating, and a picture should be emerging of the most important topics to address.

Congratulations, you now have a long list of material risk topics, ready to be turned into the final list of material issues.

Your long list should be the combined results of your earlier work, and include:

From here, you now need to set appropriate thresholds for materiality.

Unfortunately, there is no science to thresholds, but some things to keep in mind are that thresholds should leave you with an achievable number of material topics – not an overwhelming amount, or only 1 or 2 topics.

If you have been using a 1-5 rating system for the likelihood & severity of impacts, the maximum possible materiality value will be 25 (i.e. 5 * 5), and the lowest 2 (1 * 1). For a small organisation without a lot of resources, a materiality threshold might be set at 20/25, but a larger organisation of employing many thousands of individuals, and with greater organisational capacity and more stakeholder demands, might set a threshold of only 15/25. The distribution of risks for each organisation will also play a role – for companies that are less exposed to risks, or that have identified fewer potential topics, a lower threshold might be appropriate.

The SGA is currently exploring whether and how to produce future industry-specific guidance on how to establish and communicate rationales for materiality ratings in collaboration with SGA members, in ways that satisfy auditors, and that are informed by member’s experience with ESRS reporting.

Here are two examples of how an organisation might implement climate scenarios and identify physical risk impacts to be included in disclosures:

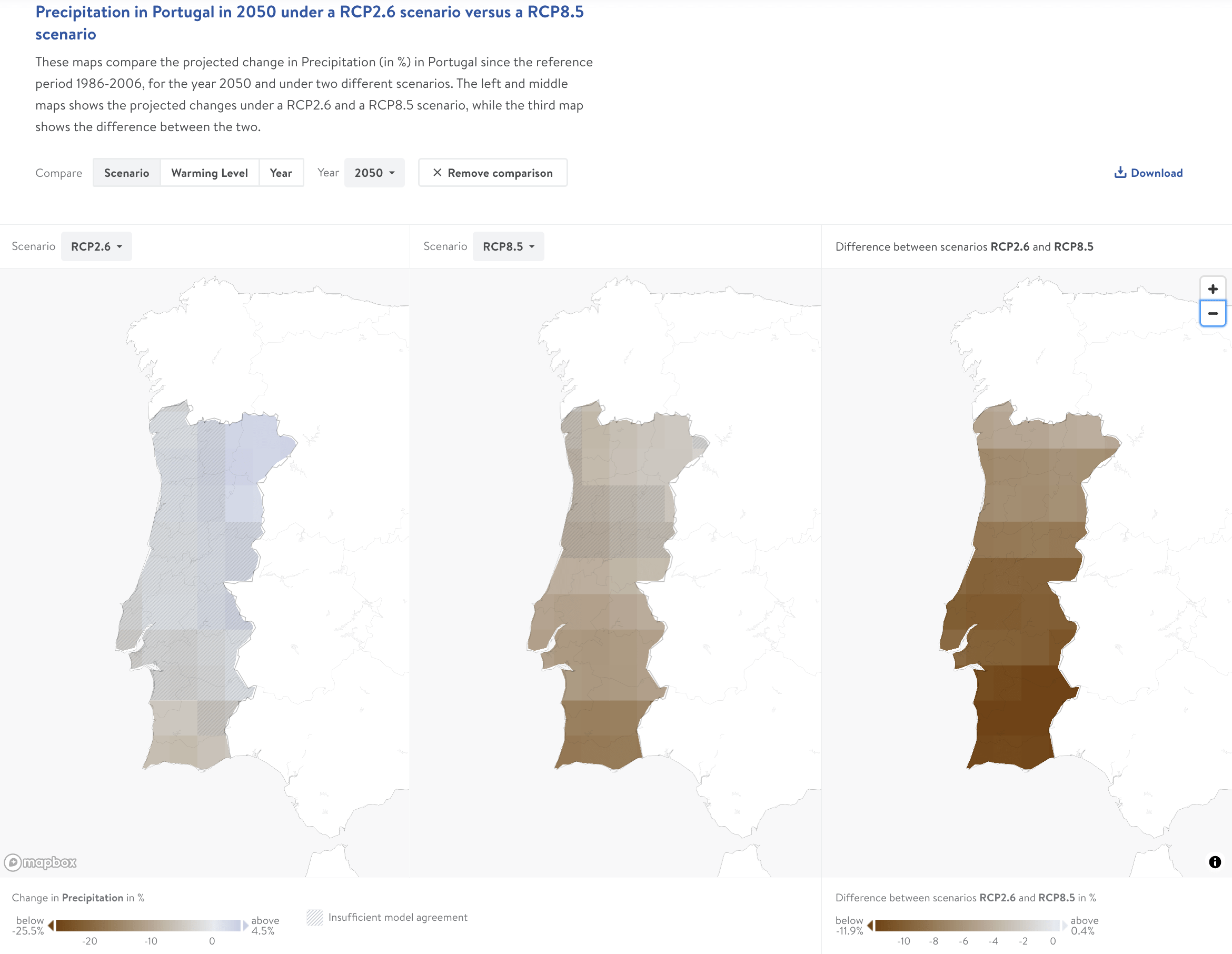

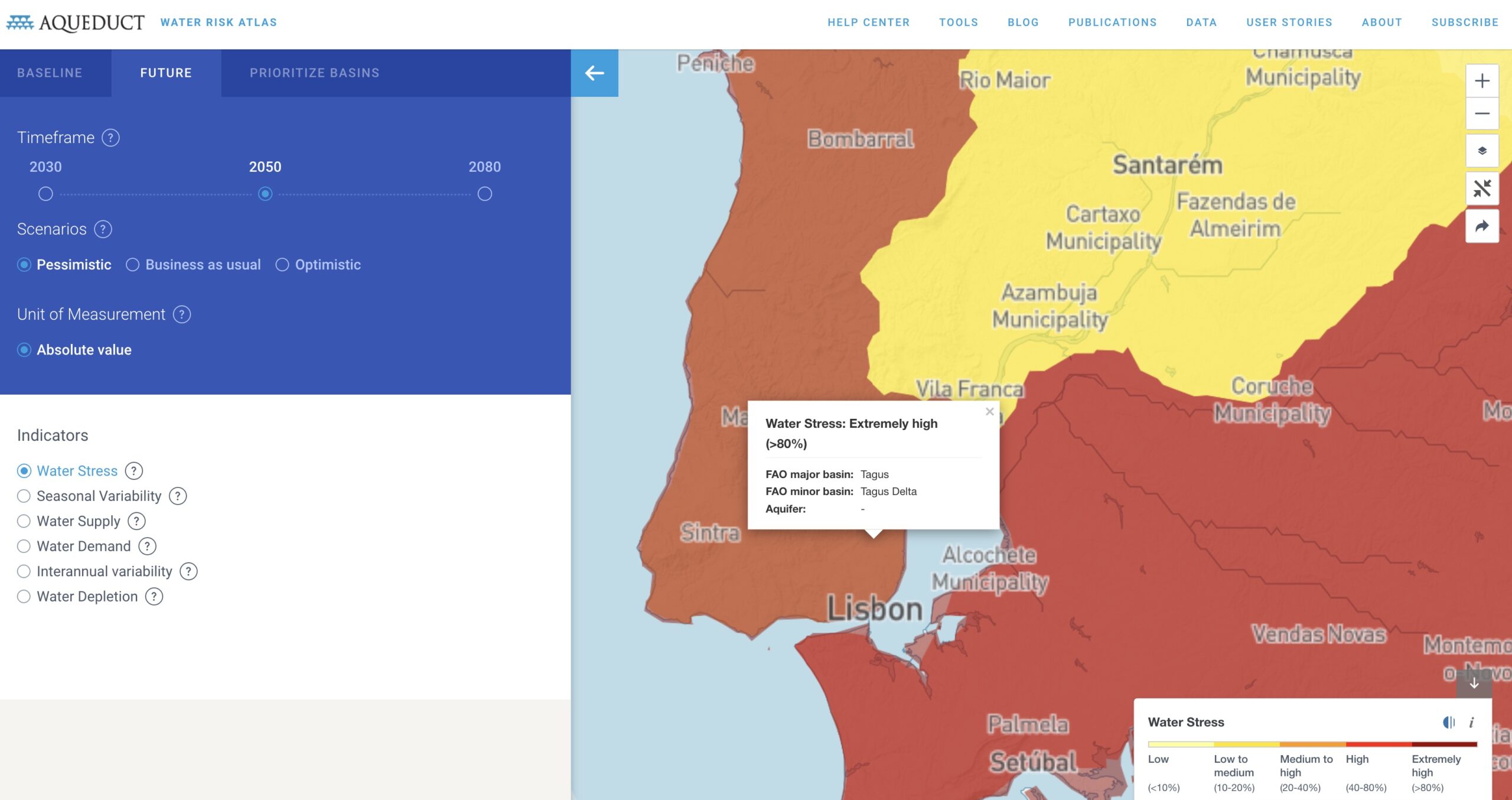

Example 1: A game development studio of approximately 200 people is located in the centre of Lisbon, Portugal. It also has a small number of employees in France and Germany who work remotely. During Stage 2: Preparation, the ESRS Preparers identified two key features of their value chain – their main office in Lisbon, a data centre that is critical to the delivery of their game also located in Lisbon and supplied by a local business partner.

With the locations of key value chain components identified, the studio conducts a scenario analysis using both RCP2.6 (low emissions scenario) and RCP8.5 (high emissions scenario). They use the SGA risk tool and work through a number of different potential impacts, looking at tools that provide future projections of the likelihood and severity of physical climate impacts on their key value chain components. Many of the physical risks are considered non-material. However, the process identifies risks associated with changing availability of water, and increasing temperatures: their main office and data centre is located in an area prone to droughts (southern Portugal), and their data centre requires water as part of their office operations and cooling systems, with the tools identifying a substantial likelihood of risks with potentially material impacts that may affect the business.

The climate impact tool used shows that in 2050, under a high emissions scenario, southern Portugal may be at risk of receiving more than 10% less rainfall per year, which the team considers to be a potential impact based on past droughts, and places on its list of physical risks – contributing to a risk of increased wildfires.

During the process, the team also considers the effect of reduced rainfall on the local water supply, noting an extremely high projected level of water stress. As their data centre partner uses a water cooling system for the data centre, they add this risk and the disruption it represents to their critical data centre to their list of physical risks to disclose.

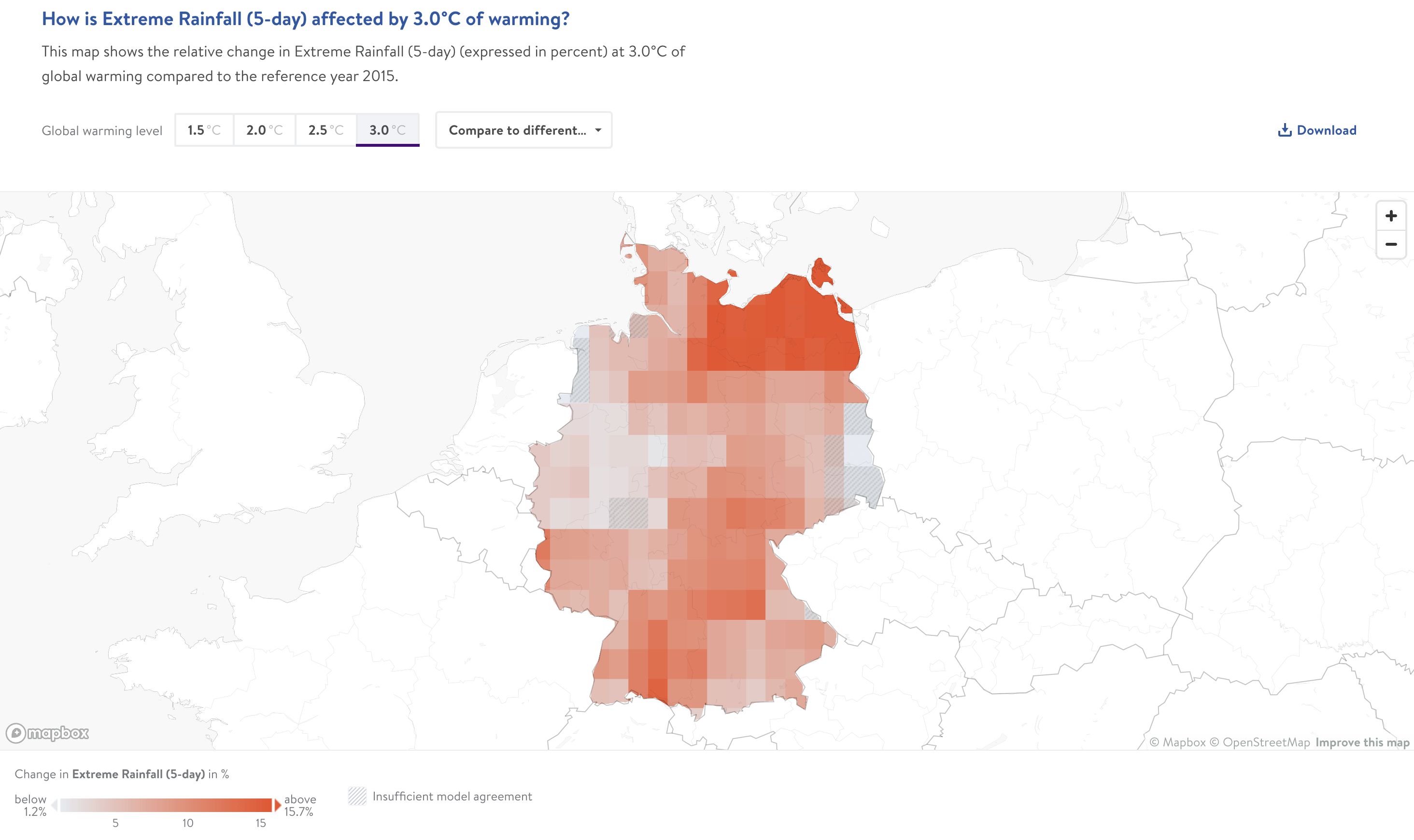

Example 2: A Hamburg, Germany-based game developer undertakes a scenario analysis, also applying the RCP2.6 and RCP8.5, using the Climate Analytics impact explorer to consider several physical impacts, many of which show little or no impact, and decide they are not material.

When they examine the changing likelihood of “extreme rainfall events”, however, they find that under the high emissions scenario the risk of “Extreme Rainfall” is 15% higher relative to the low emissions scenario. Considering that the studio is located not far from the banks of the river Elbe, the team decide that extreme rainfall and associated flooding present a potential physical risk to their offices. If extreme rainfall were to eventuate, they expect it could produce disruptions and damages to their office location. They rate the likelihood as low (2/5) however the severity would be medium (3/5) adding it to their list of physical risks for disclosure in their reporting.

The undertaking shall describe the process to identify and assess climate-related impacts, risks and opportunities.

This description shall include its process in relation to:

(a) impacts on climate change, in particular, the undertaking’s GHG emissions (as required by Disclosure Requirement ESRS E1-6);

(b) climate-related physical risks in own operations and along the upstream and downstream value chain, in particular:

(c ) climate-related transition risks and opportunities in own operations and along the upstream and downstream value chain, in particular:

When disclosing the information on the processes to identify and assess climate impacts as required under paragraph 20 (a), the undertaking shall explain how it has:

(a) screened its activities and plans in order to identify actual and potential future GHG emission sources and, if applicable, drivers for other climate-related impacts (e.g., emissions of black carbon or tropospheric ozone or land-use change) in own operations and along the value chain; and

(b) assessed its actual and potential impacts on climate change (i.e., its total GHG emissions).

When disclosing the information on the processes to identify and assess physical risks as required under paragraph 20 (b), the undertaking shall explain whether and how:

a) it has identified climate-related hazards (see table below) over the short-, medium- and long-term and screened whether its assets and business activities may be exposed to these hazards;

b) it has defined short-, medium- and long-term time horizons and how these definitions are linked to the expected lifetime of its assets, strategic planning horizons and capital allocation plans;

c) it has assessed the extent to which its assets and business activities may be exposed and are sensitive to the identified climate-related hazards, taking into consideration the likelihood, magnitude and duration of the hazards as well as the geospatial coordinates (such as Nomenclature of Territorial Units of Statistics- NUTS for the EU territory) specific to the undertaking’s locations and supply chains; and

(d) the identification of climate-related hazards and the assessment of exposure and sensitivity are informed by high emissions climate scenarios, which may, for example, be based on IPCC SSP5-8.5, relevant regional climate projections based on these emission scenarios, or NGFS (Network for Greening the Financial System) climate scenarios with high physical risk such as “Hot house world” or “Too little, too late”. For general requirements regarding climate-related scenario analysis see paragraphs 18, 19, AR 13 to AR 15.

We are constantly iterating and improving our resources. If you have feedback on any of these tools – please reach out, and we may be able to help improve your experience with them.

As the use of climate scenarios is a complex topic, the SGA offers workshops and training rather than templates. Ask us about what we can do to help skill up report preparers in the use of scenarios for your risk analysis and disclosure requirements.

The SGA physical risk template is a component of the DMA Game industry physical & transition risk + opportunities template.

The template can be found here.

The SGA transition risk template is a component of the DMA Game industry physical & transition risk + opportunities template.

The template can be found here.

The SGA physical risk template is a component of the DMA Game industry physical & transition risk + opportunities template.

The template can be found here.