The first step on your ESRS journey is to become familiar with the key concepts that the ESRS expects report preparers to understand and apply to their particular situation. The five concepts are:

Below we describe the key elements of each concept, highlighting the ways that they might differ from past understandings or expand on what you might initially expect from the term. The SGA runs a 90-minute workshop that goes into more detail on each of these concepts, as well as how they apply to game businesses. Get in touch if this is of interest to you.

In common usage, “due diligence” mainly describes an outcome – referring to the results of taking actions to minimise risk, ensure an appropriate level of care, responsible conduct, reduce negative impacts, and so on. In the ESRS, “due diligence” still has this meaning but appears more often as a noun – describing the process of due diligence.

This is important: the “ESRS do not impose any conduct requirements in relation to due diligence…” (in other words, there are no specific actions that count as due diligence or not) “…nor do they extend or modify the role of the administrative, management or supervisory bodies of the undertaking with regard to the conduct of due diligence.” (ESRS 1, 4. para 58) There is no one-size-fits-all approach that is “due diligence”, and for most businesses describing what you already do as part of risk management processes may well be enough. Where due diligence is concerned, the ESRS largely requires preparers to disclose the details of the process – including describing certain steps in the ESRS preparation process itself (see quote opposite).

So in general, organisations are not forced to change their risk and control processes as part of the ESRS – though nothing is stopping them from changing or improving either.

At various stages of the reporting process, ESRS preparers are asked to describe parts of the due diligence process – often this will be about how preparers have engaged with specific stakeholders, or how they have approached the identification of actual and potential impacts. Due diligence is a component of the ESRS 2 (the cross-cutting part of the ESRS that all companies complete) Governance sections, requiring disclosure like a statement about “information provided to and sustainability matters addressed by the undertaking’s administrative, management and supervisory bodies” – i.e. a disclosure of the types of information that gets passed to admin or management teams on ESG issues, and how they are addressed. This might involve describing the “integration of sustainability-related performance in incentive schemes”, i.e. how certain leaders have sustainability KPIs.

There are also topical ESRS sections that require disclosures of specific parts of the due diligence process. For example: many games businesses will find Topical ESRS S4 “End users/consumers” to be a material area with relevance to how you do business. In disclosure requirement S4-2 preparers are required to disclose the organisation’s “process for engaging with consumers and end-users and their representatives” – describing this as part of the “due diligence process”. If you are following the SGA ESRS Roadmap, you will be able to describe the stakeholder engagement process undertaken in Stage 2, and describe how you consider your impact on players of your game.

“Due diligence is the process by which undertakings identify, prevent, mitigate and account for how they address the actual and potential negative impacts on the environment and people connected with their business. These include negative impacts connected with the undertaking’s own operations and its upstream and downstream value chain, including through its products or services, as well as through its business relationships. Due diligence is an on-going practice that responds to and may trigger changes in the undertaking’s strategy, business model, activities, business relationships, operating, sourcing and selling contexts.”

ESRS 1.4 para 59, p. 12

The ESRS often refers to the OECD’s “Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct”, which can be downloaded here. In summary, the OECD describes ideal due diligence as follows: due diligence is preventative, can involve prioritisation, is dynamic, does not shift responsibilities, concerns internationally recognised standards of responsible business conduct, is appropriate to an enterprise’s circumstances, can be adapted to deal with the limitations of working with business relationships, is informed by engagement with stakeholders, and involves ongoing communication.

In conclusion – in later Stages of the ESRS reporting process you will describe the process of due diligence, and the interaction of these processes in a number of ways. The SGA can work with you to document and describe the existing due diligence processes you already have in place, or help identify the resources and strategies you need to adopt new due diligence processes.

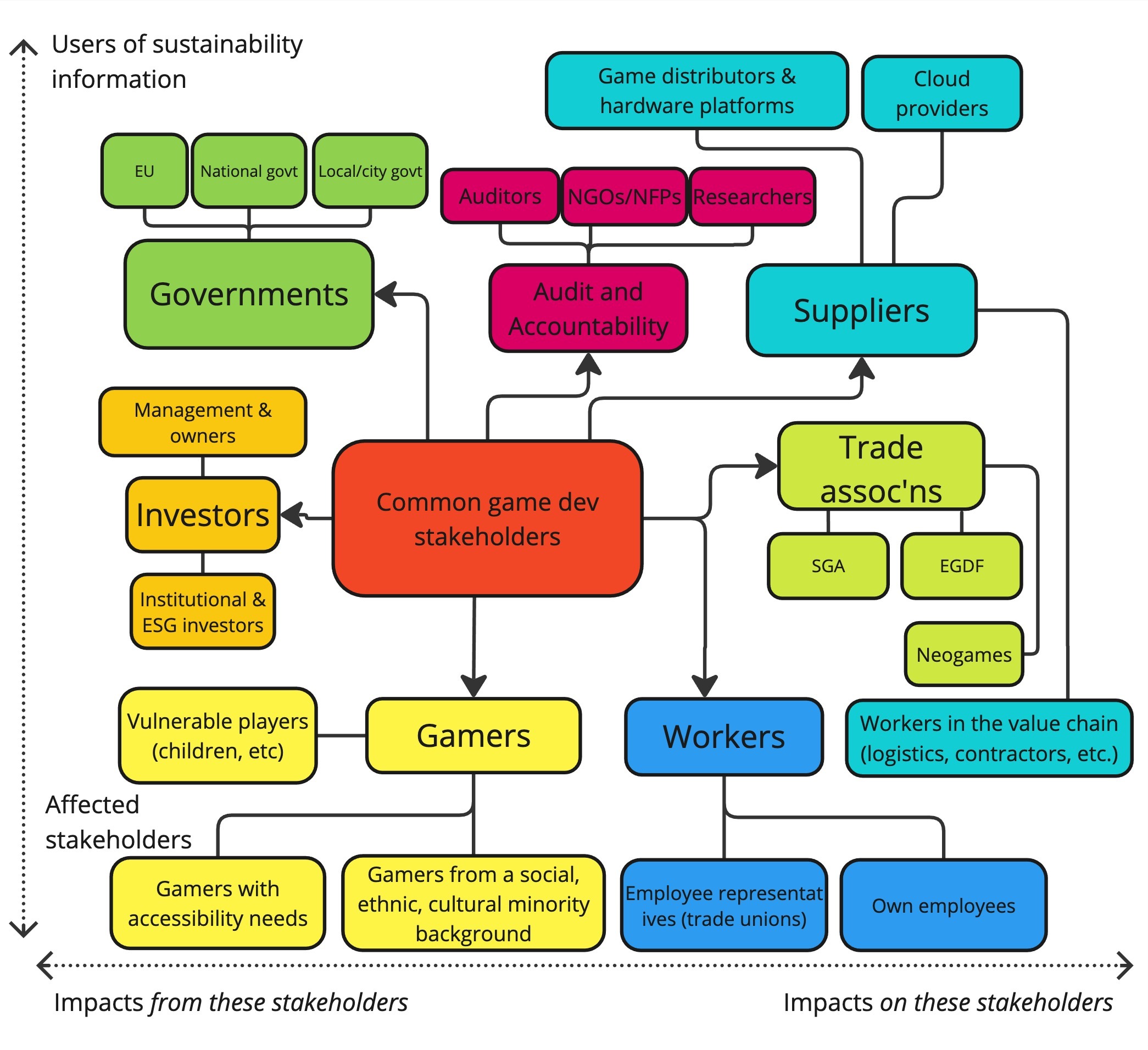

The ESRS adopts a broad definition of stakeholders – one that has been described as “people-centred” – and which goes beyond simply those with a financial interest in the success of the organisation. The key change is that a stakeholder is now anyone “who can affect or be affected by the undertaking.” (ESRS 1, 3 para. 1) This opens up a potentially long list of stakeholders, though the ESRS does not provide a comprehensive list. It does however suggest stakeholders generally fall into two groups: “affected stakeholders” and “users of sustainability statements”.

Affected stakeholders are:

“individuals or groups whose interests are affected or could be affected – positively or negatively – by the undertaking’s activities and its direct and indirect business relationships across its value chain.” (ESRS 1, Chapter 3, Section 1, para 22a)

For games businesses, this can mean end users (gamers), suppliers, workers inside the organisation, workers in the value chain of the organisation, and even local communities in and around where the organisation operates (for example, the people that live near the noisy data centre the organisation owns and uses).

While users of sustainability statements are:

“primary users of general-purpose financial reporting (existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors, including asset managers, credit institutions, insurance undertakings), and other users of sustainability statements, including the undertaking’s business partners, trade unions and social partners, civil society and non-governmental organisations, governments, analysts and academics.” (ESRS 1, Chapter 3, Section 1, para 22b)

For games businesses: this is the more traditional understanding of stakeholders, expanded to also include aspects of civil society with an interest in the responsible conduct of businesses. This might mean the local government of a city where a large games business is based, or a team of researchers focusing on the relative sustainability of the games industry compared to others.

The image above shows some of the main categories and subcategories of stakeholders possible across the games industry. Specific stakeholder positioning is for illustration purposes only and to be determined by each ESRS report preparer.

The ESRS expects stakeholders to be engaged with and have some input in the process of identifying material issues – this is a major focus of the Stage 2 process, which in turn is a key activity that informs the long list of potential material topics. These are analysed during the double materiality process (Stage 3 in the ESRS Roadmap).

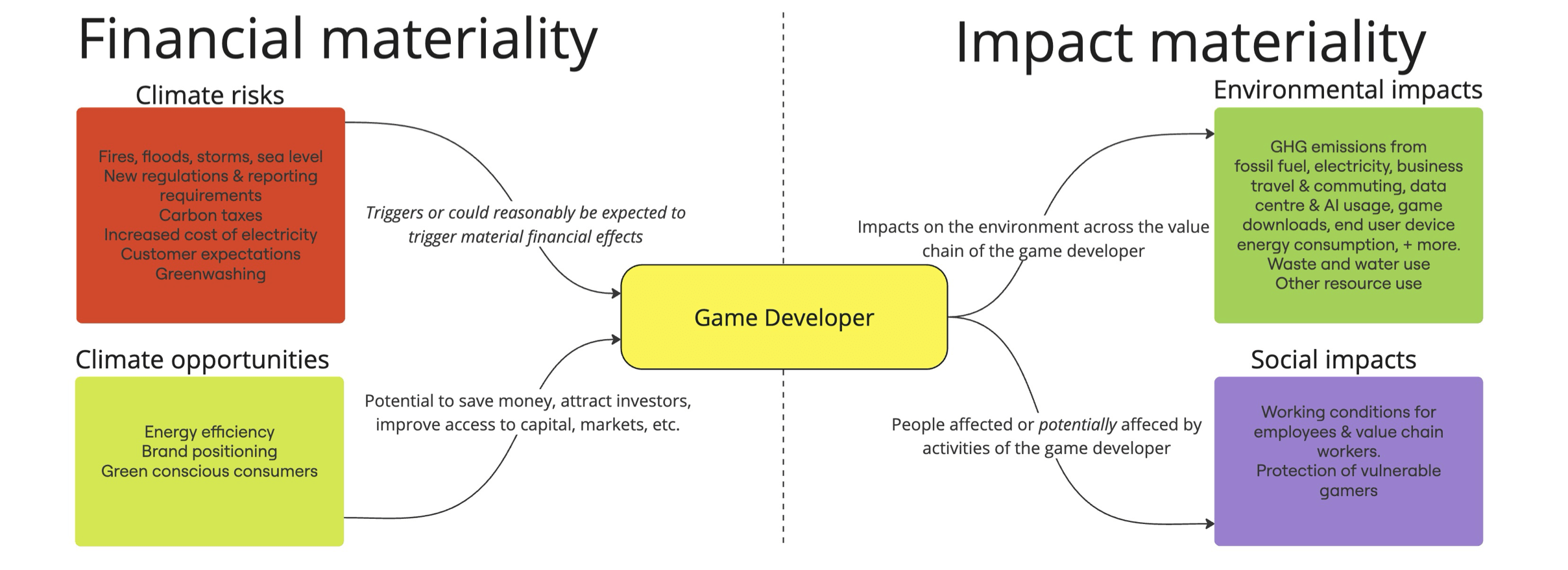

The ESRS introduces the new term “double materiality” which describes a new process of considering the impacts that people and the planet have on a business, and the impacts that the samr business has on people and the planet. This process of assessing (double) materiality “is the starting point for sustainability reporting under ESRS.” (ESRS 1.3.2, para 26.) Everything in the ESRS revolves around the double materiality assessment (DMA) process, and it is a substantial undertaking. Stage 2in the ESRS Roadmap consists of work to prepare for the DMA.

To help explain how to apply double materiality, the ESRS introduces two criteria for assessing materiality: financial materiality, and impact materiality.

Financial materiality

The starting point for financial materiality is: “the identification of risks and opportunities that affect or could reasonably be expected to affect the undertaking’s financial position, financial performance, cash flows, access to finance or cost of capital over the short-, medium- or long-term.” (ESRS 1, Appendix A, AR 14, p. 26) Financial controllers will be familiar with many of the market or reputation-based financial matters, however the financial impact of climate–based events may be new to many.

Some examples of possible financial materiality might include:

Impact materiality

The other criteria to apply is impact materiality, which considers the negative effects the activities of the business have (or could have) on the environment or people. This includes impacts on employees, workers in the extended value chain, consumers (gamers), and the general public. The ESRS provides a list of impacts to consider in the form of the “Topical ESRS” sections on environment (E1-E5) and social impacts (S1-S4), which can help provide a starting point for impact materiality. The ESRS notes, however, that the topical ESRS list is only “a tool to support the undertaking’s materiality assessment. The undertaking still needs to consider its own specific circumstances when determining its material matters.” (ESRS 1, Appendix A, AR 16, p. 26)

Some examples of impact materiality might include:

The result of a double materiality assessment will be a list of material issues, which will trigger disclosure requirements in various parts of the ESRS. Required disclosures may come in the form of metrics, targets, datapoints, or narrative disclosures. Some material issues require the disclosure of particular policies, targets and actions that will be taken to manage material issues.

The SGA can help with game industry-specific guidance about common material issues for the games industry. The SGA Standard also provides a common and applicable set of methodologies for game businesses to calculate specific reportable GHG impacts.

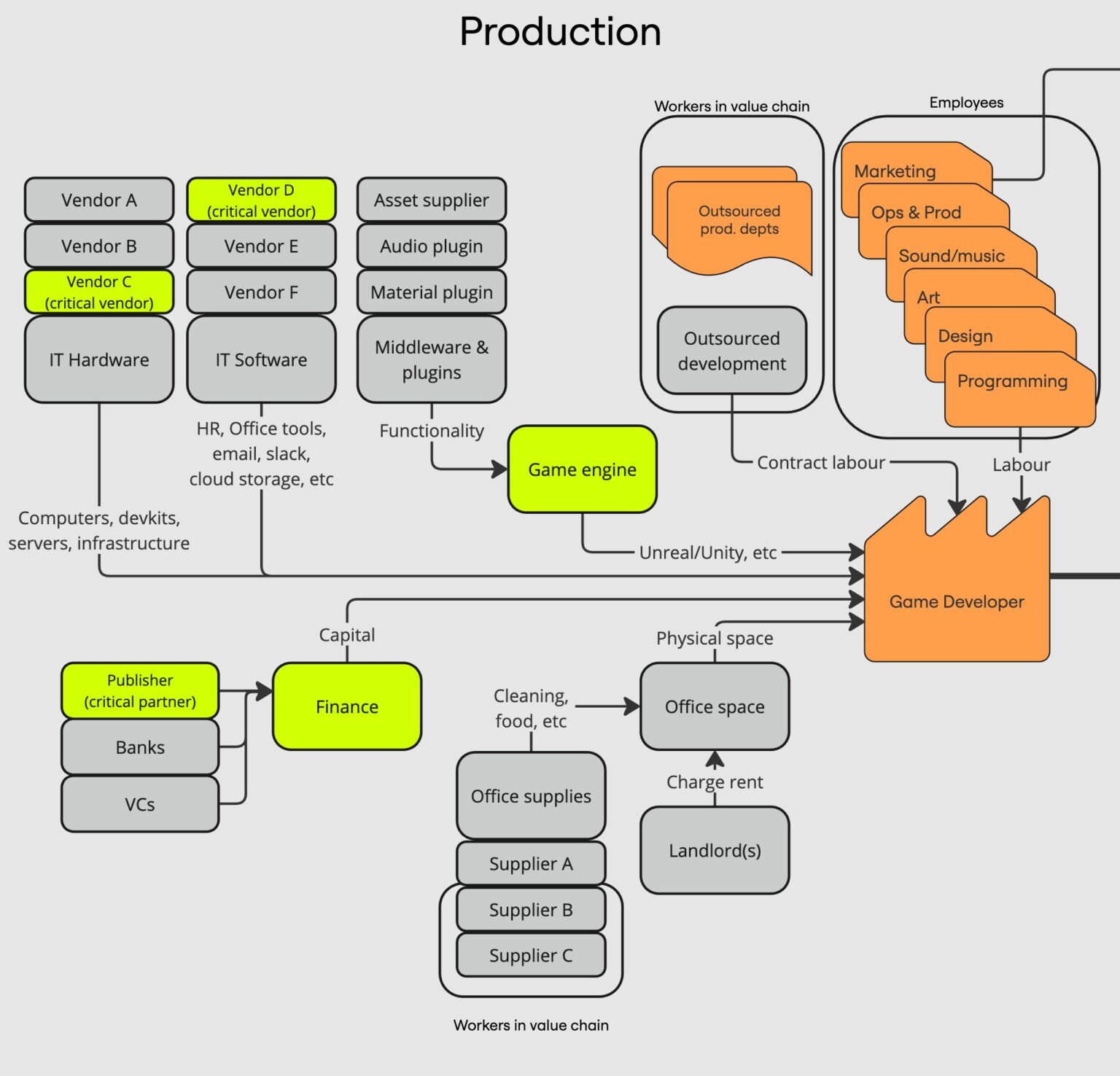

“The information…provided in the sustainability statement shall be extended to include information on the material impacts, risks and opportunities connected with the undertaking through its direct and indirect business relationships in the upstream and/or downstream value chain.”

(ESRS 1, 5.63, p.13)

The ESRS maintains the traditional understanding of the value chain – referring to all the inputs, materials, and other processes that are part of the production of a sold product. The ESRS does specify, however, it is concerned with the entire value chain – which, for complex game development, can be a long, complex mix of businesses, contractors, logistics networks, and software and hardware platforms – not to mention end users themselves. This means going beyond Tier 1 suppliers, and may mean considering their suppliers and so on up the entire value chain.

A caveat to this new focus on the entire value chain is that not all of the value chain will be relevant to sustainability matters. The ESRS only requires materially relevant parts of the value chain to be disclosed.

The ESRS:

“does not require information on each and every actor in the value chain, but only the inclusion of material upstream and downstream value chain information. Different sustainability matters can be material in relation to different parts of the undertaking’s upstream and downstream value chain. The information shall be extended to include value chain information only in relation to the parts of the value chain for which the matter is material.” (ESRS 1, 5.64, p.13)

But this still means that ESRS preparers will need to have some understanding of their business’ entire value chain – which might mean gathering some insight into the production of, for example, game hardware and devices, cloud providers, or game distributors – but only if these end up being a material issue.

Consider the following example – a large, successful console game developer of ~200 employees is conducting their double materiality analysis (Stage 3 on the ESRS Roadmap). They identify their main cloud provider as a stakeholder with the potential to have a major impact on their business – in terms of both financial materiality and impact materiality. As their sole provider of online hosting for their game, their pricing decisions can make a material impact on the cost to support their game, and as a large user of electricity, the GHG emissions of their data centres form a substantial part of their Scope 3 emissions. Because of this, the console developer may need to know and be able to disclose ceratin material dimensions of their cloud provider – such as their policies or practices about renewable electricity procurement.

One section of the ESRS requires disclosures on “policies, actions and targets” – and when these involve actors in the value chain, preparers are required to “include upstream and/or downstream value chain information to the extent that those policies, actions and targets involve actors in the value chain.” (ESRS 1.5.2.17, p.71) In the example above, the cloud provider is determined to be material to the console developer’s own policies and targets around renewable energy use – part of their plan for aligning with 1.5º Paris Agreement targets – and so discloses details of their cloud provider and their own policies and targets.

The ESRS concludes that report preparers are only required to include value chain information (like info on suppliers, their GHG targets and policies, the results of supplier engagement efforts, etc) wherever it is necessary to either:

"Sustainability information is relevant when it may make a difference in the decisions of users"

ESRS 1, Appendix B, QC1.

"Faithful representation requires information to be (i) complete, (ii) neutral and (iii) accurate."

ESRS 1, Appendix B, QC5.

"Sustainability information is comparable when it can be compared with information provided by the undertaking in previous periods and, can be compared with information provided by other undertakings, in particular those with similar activities or operating within the same industry."

ESRS 1, Appendix B, QC10

“Sustainability information is verifiable if it is possible to corroborate the information itself or the inputs used to derive it.”

ESRS 1, Appendix B, QC13

"Sustainability information is understandable when it is clear and concise. Understandable information enables any reasonably knowledgeable user to readily comprehend the information being communicated."

ESRS 1, Appendix B, QC13

The final concept that the ESRS requires preparers to keep in apply is the “qualitative characteristics of information” – this bit of jargon may sound complex, but is in reality fairly simple. It is, however, quite important, and outlines a series of guiding principles that ESRS reports are instructed to follow.

There are two aspects to the definition of characteristics of information – the first is the “fundamental qualitative characteristics of information”, which means sustainability reporting should apply a lens of relevance and faithful representation in reporting. In practice, that means representing the true sustainability position and challenges of the organisation – not greenwashing by selecting only metrics that make the organisation appear in a favourable light. It also means that non-relevant information is to be excluded from sustainability reporting.

What makes information relevant, however, requires some interpretation and will depend on the users of that information: “Sustainability information is relevant when it may make a difference in the decisions of users under a double materiality approach.” (ESRS 1, Appendix B, QC1) For example – a user of sustainability reporting like an ESG-focussed investor might find it relevant to know about a business’ screening processes for suppliers who prioritise sustainability, and this may make a difference to their decision to invest in a company or not.

The second aspect of this definition is the “enhancing qualitative characteristics of information” which means that information should enhance understanding, and do so by being comparable, verifiable, and understandable.

Comparability means that it enables comparisons with the organisation’s past reporting and performance (e.g. from past years), as well as with other companies or businesses in the same industry. For example – this might mean choosing to apply the same industry specific metrics as other game companies, like GHG emissions per headcount, GHG emissions per-hour of gameplay, or other metrics enabled by the SGA GHG Standard. This does not mean being locked into one reporting methodology for all time – but it means making efforts to ensure comparability between reports and across the industry as much as possible.

Regarding verifiability of information: “Sustainability information is verifiable if it is possible to corroborate the information itself or the inputs used to derive it.” (ESRS 1, Appendix B, QC13) It also means that “various knowledgeable and independent observers could reach consensus, although not necessarily complete agreement, that a particular depiction is a faithful representation.” (QC14) This means being transparent about calculation methodologies, providing corroborating evidence available to other users (such as industry-wide averages or SGA collected data).

Lastly, understandability requires that sustainability information be “clear and concise” and “avoid generic “boilerplate” information, which is not specific to the undertaking” and communicated in such a way that “allows users to relate information about its sustainability-related impacts, risks and opportunities to information in the undertaking’s financial statements.”

Remember: the ESRS’s goal is to provide meaningful, specific disclosures about companies and their specific sustainability context and to do so in a way that places this reporting on an equal footing with financial reporting. This makes sense when we consider the increasing impacts of climate change, biodiversity loss, and other sustainability challenges facing business worldwide.