In this stage, we are gathering the necessary information to be used in Stage 3 – Double Materiality Analysis. Preparers will also begin an ongoing engagement and consultation process with stakeholders – or more likely, improve and refine their existing process.

The three components of Stage 2 – Preparation can be done somewhat in parallel. Though Stakeholder engagement is the most critical (as it is essential to generating the list of material issues for analysis in the DMA process in Stage 3) it is also an ongoing process without a fixed “end”. The stakeholder engagement process will be improved and informed by having a clear understanding of the business value chain and its strategy and business model. All three of these activities are closely interrelated. The strategy and business model determine the way the business generates income and profit (for example: by making F2P hypercasual mobile games, or by selling development services to another company) which in turn mobilises a value chain to produce that game product (the workers who make the game, but also: suppliers, publishers, financiers, distributors, hardware platforms, and end consumers).

The goal of describing your strategy is to enable users of sustainability information to identify where these relate to or affect sustainability – both actually and potentially. For this, the ESRS specifies (in ESRS 2, SBM-1, para 40) the following four elements:

1 significant groups of products and/or services offered, including changes in the reporting period (new/removed products and/or services);

2 significant markets and/or customer groups served, including changes in the reporting period (new/removed markets and/or customer groups);

3 headcount of employees by geographical areas; and

4 where applicable and material, products and services that are banned in certain markets;

Below are example descriptions for three different kinds of game developers, and their hypothetical strategy and business model descriptions.

1 Developer A produces the “Farm Sim” series of games, first launched in 2012, a free-to-play farming simulation game that is monetised through in-app purchases of an in-game currency.

The current entry in the series “Farm Sim 4” is being actively developed with a live service model and seasonal releases.

The franchise has been the main revenue source for Developer A since 2012, however in 2025 (the reporting year) the business also launched a new IP series “Space Gatcha Extreme” during the reporting period (e.g. a game launched during 2025) which is also F2P hypercasual game, monetized through in-game advertising and in-app purchases of an in-game currency.

1 Developer B produces the “Devil May Shoot” franchise games, which it first released on PC in 2008. There are now eight instalments in the Devil May Shoot” series, with “DMS8” being released in 2021 for PS5/Xbox Series & PC. The main franchise games are premium-priced single-player games with an increasingly important multiplayer feature. Games are sold via both physical retail and digital download. A growing percentage of revenue is derived from the sale of cosmetic items, and a season pass expansion for the multiplayer.

2025 saw the successful launch of three new Seasons of DMS8, which maintained high engagement with existing players.

1 Developer C is a work-for-hire studio that develops 2D and 3D art assets for client developers. Based in Łódź, Poland, Developer C has made a name for itself by working on major AAA releases on console, PC, and mobile for several first-party developers, and has three contracts for assets for in-development games,

In 2025, the business began selling art asset packs on the Unity and Unreal stores, which have seen modest success and sales are on an upward trajectory.

2 “Farm Sim 4” is currently available in European, North American, and Asian markets via the Google Play store and the Apple App store. “Farm Sim 4” primarily targets the demographic of 25-40 y/old women who enjoy hypercasual farming games.

“Space Gatcha Extreme” is is available in the same geographic markets as “Farm Sim 4”, however it targets a new demographic of 18-30 year old male gamers on mobile who enjoy fast-paced shoot-em-up gameplay with a Gatcha element.

Note: The high level of detail in the description above may seem excessive, but it may be pertinent if it reveals important stakeholder groups to consult on the impact the organisation might have on them. For example: the particular customer groups for Farm Sim 4 and Space Gatcha Extreme could be impacted by particular monetization strategy, loot box drop rates, etc. or it may reveal a significant group of customers who can only be served by particularly GHG intense infrastructure.

2 “Devil May Shoot 8” is available worldwide on PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series consoles, with substantial player bases in North America and Europe. “DMS8” continues to target the “core gamer” demographic, delivering fast-paced FPS gameplay that relies upon visual identification of targets in a complex and changing environment. DMS8 players are predominantly male, between the ages of 14 and 30, and enjoy the combination of rapid twitch FPS gameplay and strategic team-based multiplayer with voice communications.

Note: The description above provides enough detail to inform potential material issues for certain affected players groups – for example, players from a social, cultural or ethnic groups other than the majority who may be exposed to player harassment in a team-based environment, as well as potentially highlighting vision related accessibility in the fast-paced FPS environment as a material issue for some players (e.g. with colour blindness).

2 Main markets for development services are first and third-party developers of AAA console, PC and mobile titles. Current customers are large, multinational North American and game businesses, however a strategic shift towards asset pack creation is also underway with increasing potential for sales on Unity and Unreal stores. One current contract with a large European mobile developer is up for renewal in late 2026, which would extend current work on an unannounced game project.

Note: The description above provides enough detail to allow users of sustainability information to understand that the main customers of the studio are not players but other developers. As a WFH studio that does not interface with gamers, they may not have any stakeholders in this category. If they began developing their own games in the future, they would have to revisit this and expand their stakeholder list to include gamers.

3 Game Developer A has 95 employees in Denmark, 30 employees in France, 10 employees in Brazil, 5 employees in Russia, 5 employees in the United States.

Note: This information could also be presented in the form of a table.

3 Developer B has 200 employees in Finland, and 10 employees in the United States.

Note: This information could also be presented in the form of a table.

3 Developer C has 120 employees in Poland, 50 employees in China, 30 employees in Indonesia, and 12 employees in Germany.

Note: This information could also be presented in the form of a table.

4 This topic is unlikely to apply to the majority of game businesses (unless your business also makes weapons, tobacco products, or is in the coal, oil, or gas industries) – one exception may be if your business is producing real money gambling products.

4 This topic is unlikely to apply to the majority of game businesses (unless your business also makes weapons, tobacco products, or is in the coal, oil, or gas industries) – one exception may be if your business is producing real money gambling products.

4 As the company is not engaged in any other activities besides work-for-hire game development, this topic does not apply.

These are just the bare essentials to include in your description of your strategy and business model. If your organisation has a specific strategy that leadership has set – for example, pursuing a competitive advantage or maintaining a particular market niche – by all means, write that down as well as it may influence or inform the analysis in Stage 3 (double materiality analysis). Anything that might “make a difference” to a user of sustainability information – an investor, an analyst, or an auditor – can be recorded here and used in later stages.

If your organisation has an existing sustainability strategy – such as a focus on digitalization and phasing out of physical boxed game sales – record that as well.

“The information…provided in the sustainability statement shall be extended to include information on the material impacts, risks and opportunities connected with the undertaking through its direct and indirect business relationships in the upstream and/or downstream value chain.”

(ESRS 1, 5.63, p.13)

Understanding your value chain starts with understanding the structure of the business. While a “supply chain” is all about how goods and services move through the production process to a customer, the value chain adds consideration of “the manner in which value is added along the chain, both to the product / service and the actors involved.” (Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership)

For example: a paid Unity plugin might add features to the engine which save the engineering team time developing their own solutions – in this way, it adds value through time saving, and in turn the plugin creator recieves value: primarily the cost of the purchase of the tool, but perhaps other value, like the ability to advertise its use in the production process of a popular game. NB: It is not necessary to go to this level of detail in understanding all aspects of the value chain, but it may be worth keeping this reciprocal aspect of “value” in mind.

This is the “business school” definition of the value chain, and the GHG Protocol also offers its own explanation, focussing on key elements to be included within the boundaries of the value chain:

“value chain refers to all of the upstream and downstream activities associated with the operations of the reporting company, including the use of sold products by consumers and the end-of-life treatment of sold products after consumer use.”

GHG Protocol, 2011: Corporate Value Chain (Scope 3) Accounting and Reporting Standard, p.141

The exact steps involved in mapping the value chain will vary from organization to organization, but there are a few elements that will always be required. These include:

Below we outline two approaches to map the value chain of an organization, with a slightly different approach in each. Remember, there’s no one “correct” way. Both approaches divide the relationships into stages, with the first taking a “generic” stages approach, and the second focussing on the three main stages of game making.

Approach 1 – Upstream/Self/Downstream:

This approach might be more suitable for less complex value chains – particularly developers of games without large, complex online infrastructure for gameplay.

The second approach takes in all the same elements but guides our analysis via a slightly different division of the production process into stages. Both should produce similar results.

Approach 2 – Production/Distribution/Play:

This approach might be more useful for identifying more elements of the complex network, at the risk of overidentifying stakeholders – with a detailed and complex value chain the result, which might prove difficult to fully consider engaging with.

Once you have identified your value chain, and the key elements of it, you can start to engage with stakeholders across the value chain.

Next steps:

Feel free to start with the SGA value chain diagram – which can illustrate the typical inputs, processes and partners across the process of game development, game distribution, and game play. Alternatively, for simpler value chains, you can simply make a list of the major elements of it.

The SGA has prepared the following template Value Chain map that can be adapted to reflect the findings of your own value chain analysis.

The resource can be accessed as a Miro board at this link.

With a clear understanding of our strategy & business model, together with the shape of the value chain, we can begin identifying stakeholders and the process of engaging them.

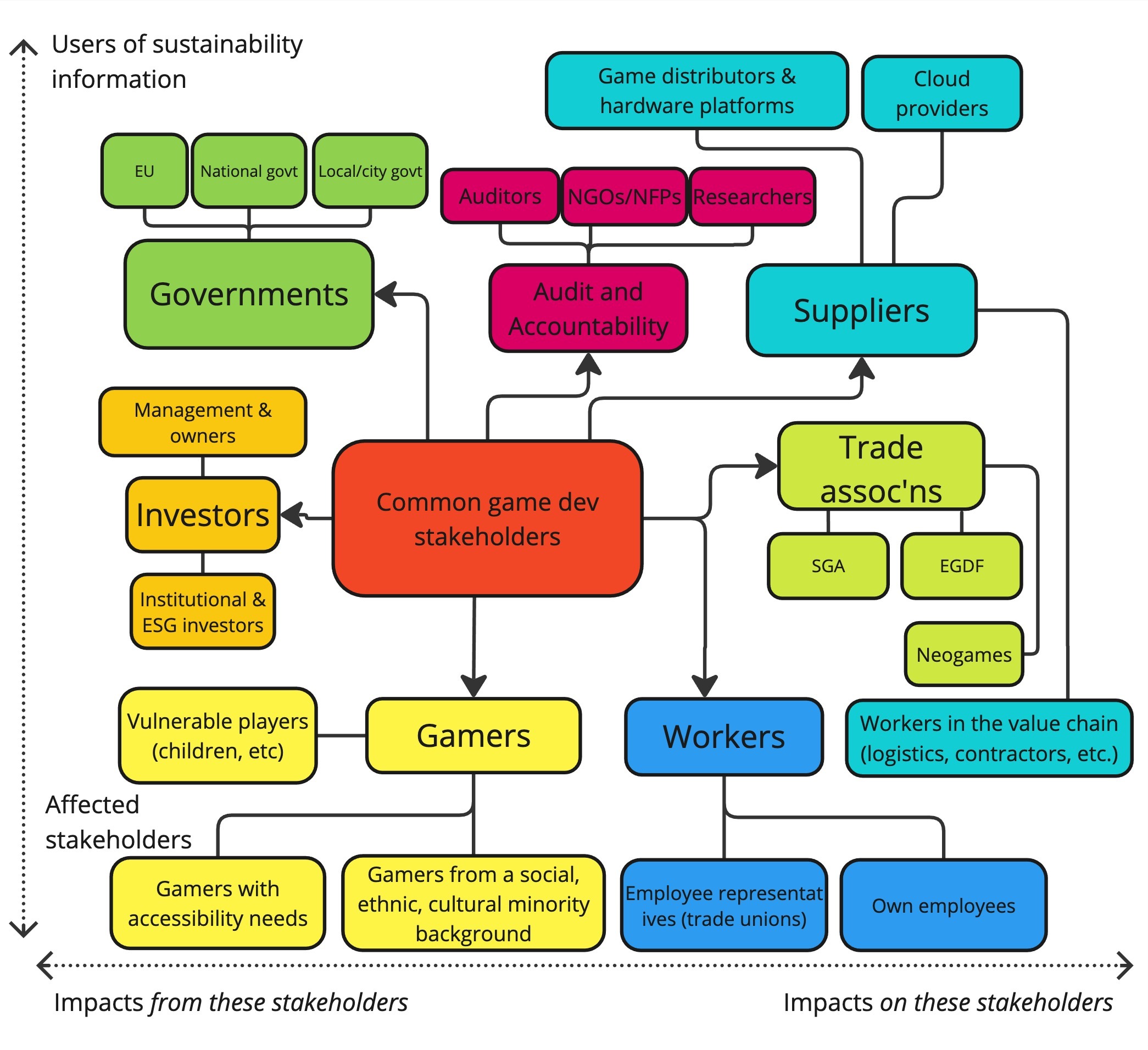

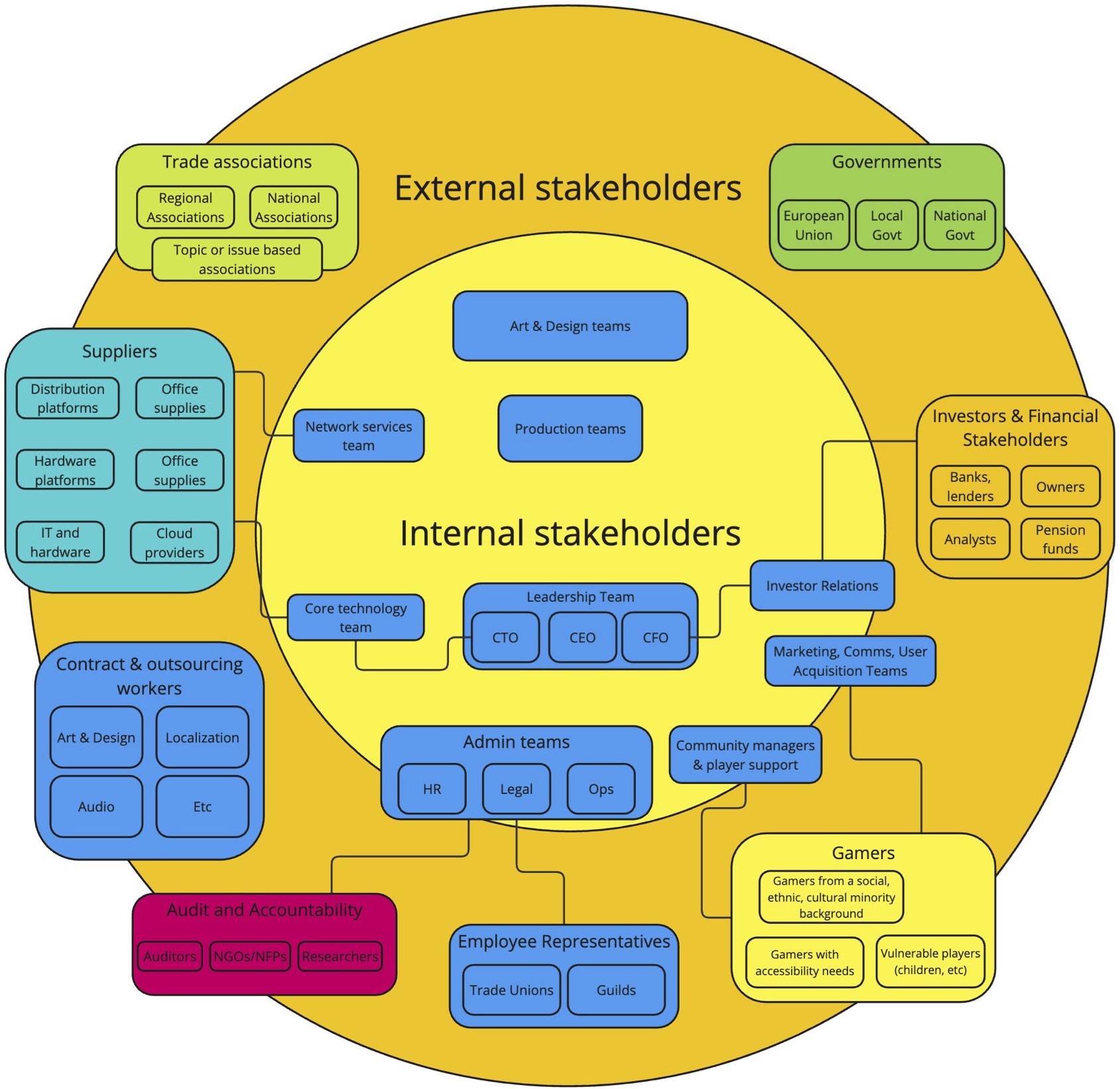

A quick reminder that stakeholders are anyone “who can affect or be affected by the undertaking” (ESRS 1, 3 para. 1) and they are grouped into two main categories: affected stakeholders and users of sustainability information – and it is possible to belong to one or both. So we are considering stakeholders through the lens of who can affect or be affected by the organization, and who the users of our sustainability reporting are.

Most companies will already have some practice at engaging with stakeholders – whether that’s internal stakeholders (teams and groups of employees, leadership teams, legal, business admin, etc) or external (customers – gamers! – as well as investors and lenders, to key business partners like platform owners). For smaller or newer businesses, this may be a brand-new process.

The image above shows some of the main categories and subcategories of stakeholders possible across the games industry. Specific stakeholder positioning is for illustration purposes only and to be determined by each ESRS report preparer.

For game companies, there are a few main groups stakeholders will fall into (with potential sub–groups) that should be considered for whether they may impact or be impacted by your organization. None of these are mandatory to include in your list of affected stakeholders, and this is not an exhaustive list, it is just a series of suggestions to inform your approach:

Remember that this list of “affected” stakeholders should be inclusive not just of people or groups your organisation might affect, but also the ones that might affect your organization – impacts can travel in both directions.

You may also wish to make a note of stakeholders’ level of importance by assessing already the scale of (actual and potential) impacts you already know about. Some stakeholders will immediately jump out as critical or very important. These are stakeholders with the ability to dramatically impact the organisation. For example: Apple or Google are likely critical stakeholders for mobile game developers, with decisions about platform rules creating substantial impacts for developers. An example in the other direction: those who depend on the organisation to ensure they are not impacted may include employees who can be impacted by changes in workplace culture or policies.

Once you have a list of stakeholders to engage, you can start to consider the most appropriate method to do so.

The ESRS does not specify how stakeholders must be engaged, but it does emphasise the importance of engagement, so we should spend some time making sure our process is fit for purpose and clearly documented:

“Engagement with affected stakeholders is central to the undertaking’s on-going due diligence process… and sustainability materiality assessment. This includes its processes to identify and assess actual and potential negative impacts, which then inform the assessment process to identify the material impacts for the purposes of sustainability reporting.”

(ESRS 1, 3.1, para 24)

To decide how to engage with particular stakeholders, we need to remember why we are engaging them in the first place. The purpose of “consultation with affected stakeholders [is] to understand how they may be impacted.” (ESRS 2, IRO-1 para. 53 (b) (iii).)

The same section of the ESRS also specifies that consulting “external experts” may need to be part of this process, to understand the risks that people might face from the business’ activities since not all stakeholders will be aware of a full range of impacts. For example, players may not be the best placed to understand what sorts of impacts they might be at risk of. Instead, organisations and groups that research player safety may be more productive to engage with.

The kind of engagement appropriate for each stakeholder will vary, so some judgment will be required. Below is a list of some suggested types of engagement, with examples for where they might be appropriate.

Types of engagement to consider:

For groups of stakeholders that contain numerous or large numbers of people, it may be best to engage representatives of stakeholders and experts who know the group well. For many game developers, if you have a community management or support team – these will be the people who most directly interface with gamers on a regular basis. The role these teams play is dedicated to engaging with end users or players, so they should be an important source of information about this stakeholder group, and the engagement process that your organisation is already engaged in with them.

When you engage any stakeholder and begin to identify impacts, make a record of the following:

The SGA has produced a template (with examples) for identifying and engaging stakeholders, and recording the identified impacts, conveniently formatted precisely for the process. It also contains example impacts to demonstrate the use of the template.

If you use the SGA template, it will also be usable for the next stage on the ESRS Roadmap: Stage 3 – Double Materiality Analysis.

We are constantly iterating and improving our resources. If you have feedback on any of these tools – please reach out, and we may be able to help improve your experience with them.

SGA Strategy and Business Model template, with examples.

SGA Value Chain map template can be accessed as a Miro board at this link.

SGA stakeholder identification and engagement template can be accessed here.